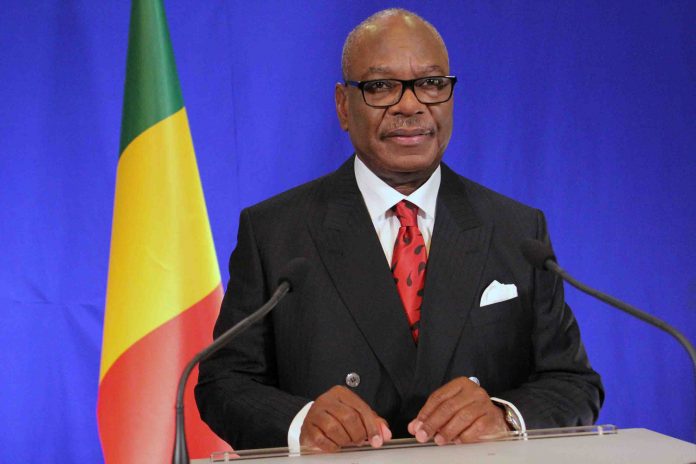

Until now, he had been considered the country’s strongman. Kidnapped Tuesday by soldiers, Ibrahim Boubacar Keïta is no longer the president of Mali. During the night of Tuesday to Wednesday, he was forced to announce his resignation himself on national television ORTM. The African Union (AU) on Wednesday demanded the “immediate release” of President Keita, as did the European Union (EU), which also called for the “return of the rule of law” in Mali. As for the United States, they denounced, through the voice of the head of the diplomacy, Mike Pompeo, a “seizure of power by force”.

More than eight years ago, in March 2012, it was his predecessor, Amadou Toumani Touré, who was also overthrown by the army, accused of “incompetence” in the face of an offensive by Tuareg rebels in northern Mali. The crisis had then led to the French operation “Serval” in Mali, followed by the election of Ibrahim Boubacar Keïta in August 2013. To better understand what the “coup d’état” that has just taken place means, we interviewed Bintou Koné, an anthropologist and researcher at the Institute of Human Sciences in Bamako.

Between Amadou Toumani Touré and Ibrahim Boucabar Keita: Is history repeating itself?

There is a link, but the two contexts are different. In March 2012, Amadou Toumani Touré was overthrown because he had failed to resolve the crisis in the north of the country, which was then under attack by Tuareg rebels with the involvement of jihadist groups. Ibrahim Boucabar Keita’s promise was to restore order, but the situation worsened. Whereas at the time the problem was confined to the north of the country, now the center is also occupied by terrorist groups, abandoned by the State. Now there is not a region where there is not an attack.

But the security situation does not explain everything to the current crisis. Malian schools have been out of order for three years and, since 2012, in some areas in the north of the country, there are no more schools. Public schools are being abandoned. As for private schools, they are inaccessible because they are too expensive for ordinary citizens. Young graduates are unable to find work, despite their training. Malians have the impression that their country is no longer developing because of corruption and impunity.

How do you explain the fall of Ibrahim Boubacar Keita, who was elected in 2013 and then re-elected in 2018 with 67.7% of the vote?

There is a crisis of confidence between the Malians and the government. The demonstrations that have been taking place in the country since June have brought together a whole series of discontent, against the political system and the governance of the country as a whole.

If this struggle is not specifically aimed at IBK, the legislative elections in the spring were the straw that broke the camel’s back. Already in 2018, his re-election was contested. There, some results were annulled by the Constitutional Court in areas where the opposition had won. The appointment of the President of the National Assembly of Mali, a friend of IBK’s son, was then highly contested. The fact that the Prime Minister, Boubou Cissé, was reappointed when he was due to resign following the killings of 11 and 12 July 2020, also sent a very bad signal. In the end, it was IBK and its system of governance that was to come to an end for the M5. A large part of the youth and some of the leaders of the M5 wanted him to resign altogether.

In such a context, how is the army coup perceived?

In July, the demonstrators at the home of Imam Mahmoud Dicko, who leads the opposition movement, had been subdued by the army. Today, the military is changing its position. Since the street has not succeeded in forcing the president to resign, it is as if the army is now coming to his aid. This is the continuation of a popular struggle that lasted for months.

This initiative by the army is therefore rather well received by the population. The army is considered apolitical. And we can see that the arrest of the president, ministers and certain members of parliament was well planned and well carried out, in the sense that everything was done to ensure that no violence would erupt. The army also called on all levels of civil society, political parties, rebels, and the international community to organize a period of civilian political transition.

It is likely that, as in 2012, power will eventually be handed back to society [the departure of Amadou Toumani Touré, overthrown by the military, was followed by a presidential election]. Hence my doubts about the concept of a coup d’état: the term is perhaps not the most appropriate in our context, because the removal of IBK comes in this case largely from the will of the street.

Source: 20 Minutes