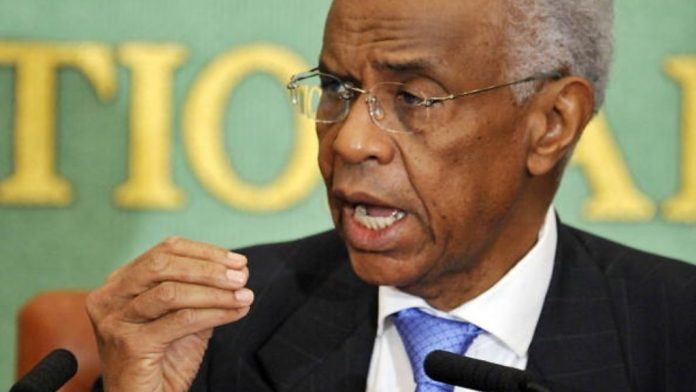

What exit from the crisis should be envisaged for the G5 Sahel countries and France, which is supposed to be met February 15? First, to reaffirm the unity and solidarity between allies and find an end to the conflict, says Ahmedou Ould Abdallah, former United Nations special representative, who chairs the Center for Strategies for the Security of the Sahel Sahara (Center 4s).

Since the rebellions of the 1990s, the regional dimension of the Malian conflict has continued to assert itself, extending beyond borders, including towards the gulfs of Benin and Guinea. From attempts at secession, in 2012 it turned into a regional and today international conflict. It kills, displaces populations, feeds refugee camps and feeds the most worn-out demagoguery and demagoguery.

The intrusion of social media has widened its front beyond the region. The longer it lasts, the more it generates the multiplication of external actors whose presence does not necessarily facilitate settlement, as we can see today in Libya, the Central African Republic and specifically in Mali. With sometimes conflicting agendas, these external actors are helping, in spite of themselves, to perpetuate the crisis they have come to help resolve. Their calls for “coordination and harmonization of priority actions to be undertaken” remain wishful thinking.

Avoid the status quo!

Faced with these dynamics, fueled for eight years by the ambiguity of the messages, what should the N’Djamena summit propose for a way out of the crisis? Reaffirming the unity and solidarity among allies and finding an end to the conflict seems the way forward.

The solidarity and success of the allies requires first of all the improvement of the national and regional security environment. For many years, this has been the field of interference by regional powers and especially mafia activities, much less mentioned, but also formidable.

To avoid deficiencies and attempts at separate settlements, a measure of high symbolic value should be taken quickly. So it would be important to stop soliciting the services of individuals perceived as pillars of a fifth column linked to trafficking and terrorism. These pyromaniac firefighters are known in the Sahel as “those who steal with thieves and investigate with the police”.

Some are suspected of double play during the assassinations of the Algerian consul general in Gao, Boualem Saies and French journalists Ghislaine Dupont and Claude Vernon, to name just the three victims. Involving them in the management of the conflict is tantamount to asking them to kill their goose that lays the golden eggs. To move away from it would clean up an environment already perverted by corruption that paralyzes good local and international intentions.

Every war must end!

Strengthening the image of the G 5 Sahel and of France will facilitate the way out of the crisis. By discernment, states will agree to end a war, and to end it together. A war where armies fight on two fronts. That of terrorist groups and their international allies sometimes, curiously, close to certain local governments.

The second front, that of bad governance, which is more pernicious, is firmly rooted. Its fuel, corruption, remains endemic and unpunished. This corruption and the carelessness which lubricates it increase every day more the number of discontented including in the armies. And the ranks of the rebellions are increasing.

With these sanitation measures, the populations and the security forces will feel more concerned by the conflict. The need to put an end to it in a credible manner will prevail over official declarations that are difficult to honor although often announced as imminent, such as the deployment in Mali of forces from ECOWAS and the African Union.

This cannot be done without significant funding, four-fifths of which are currently being provided by the European Union and the United States. The recurring statements, suggesting the contrary, can lure the troops on the front line but boost the morale of the terrorists.

Ending the war in Mali must be prepared with insight and as one general said, “the goal of war is not the prolongation of indecision.” Negotiating with the jihadists remains an option often mentioned or even already engaged.

However, as in Algeria, Afghanistan, Somalia, Chechnya and Yemen, when it comes to talks, terrorists usually have just one item on the agenda: It’s all or nothing. In Mali, where several rebel groups operate, the situation could be more nuanced.

In N’Djamena, for the G5 Sahel and France, barring any mishap, an exit deadline is already available: the end of the Transition in 2022. It would be wise to do everything so that this year, the Bamako’s future power, freed from the burden of a ten-year-old conflict, can begin the work of reconciliation. And that friendly countries, in particular France, which deploys thousands of soldiers and other allies there, preserve their image and engage in the reconstruction of the peaceful Sahel.

Reference: https://newafricanmagazine.com/25364/